Abolishing feudal serfdom was a historical choice (I)

This year marks the 60th anniversary of democratic reform in Tibet. The democratic reform abolished the feudal serfdom, which had been in place for hundreds of years in Tibet, and millions of serfs were liberated.

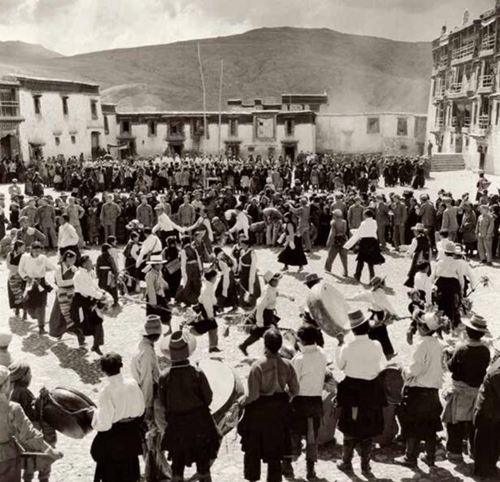

Joyous former serfs at Lhagyari Estate (1959). Photo by Lan Zhigui

Tibet’s feudal serfdom, which combined religion and politics, came about in the 12th century and developed to its peak in the 17th century. Before the democratic reform, all powers and interests were controlled by government officials, aristocrats, and high-level monks. The masses basically had no political rights, economic status, or personal freedom.

The “Thirteen Codes” and the “Sixteen Codes” formulated by the feudal serfdom were important tools by which “the three ruling groups” maintained their interests and strict social hierarchy, oppressed serfs, and trampled on human rights. The Codes divided people into three classes and nine levels. “People are divided into upper, middle, and lower classes, and each class is divided into three levels.” The Codes clearly stipulated that goldsmiths, silversmiths, blacksmiths, butchers, and beggars made up the lowest group of people. Tibetan women were also among the lowest-ranked people according to the Codes. In these strict classes and levels, it was impossible for people in the lower classes to overcome the boundaries established by the Codes. However, the rights and interests of “the three ruling groups” were sacred and inviolable according to the Codes. If a serf violated the interests of “the three ruling groups”, the Codes stipulated: “According to the crime, cut out his eyes, peel skin off his legs, cut out his tongue, cut off his hand, push him off a cliff, throw him in water, or kill him.”

A “criminal” in shackles begging on the street (1956). Photo by Chen Zonglie

The ruling class in Tibet, with its possession and monopoly of the land, pastures, and other means of production, established a relation of bondage with serfs, forcibly exploiting and enslaving them. At that time, there was such songs among serfs as: “Even if the snow mountain turns into butter, it is still owned by the lord; Even if the river turns into milk, we still cannot drink it.” According to pre-democratic reform statistics, Tibet had about 3.3 million ke (1 ke equivalent to 0.16 acres) of land, of which officials held about 38.9 percent, monasteries and high-ranked monks 36.8 percent, and the nobility 24 percent. Only 0.3 percent of this cultivated land was held by a very small number of peasant farmers in remote areas. Besides, nomads controlled most the pastures. In addition, this system of bondage was strongly protected by the feudal serfdom where religion and politics were combined. The local Tibetan government regulated that serfs could only remain on the estate lands to which they were bound, and they were not allowed to leave without permission; it was absolutely forbidden to escape. The lord of the estate also treated serfs as personal property and used them in gambling, trading, making transfers, gift giving, paying debts, and for exchange.

The ruling class in Tibet also exercised strict spiritual control through religion and controlled serfs’ spirits with illusionary ideas of a “bliss world” and “happiness in the afterlife” to enslave them. Any ideology or culture that contradicted the interests or ideology of the ruling class was considered heresy. The famous modern Tibetan scholar, Gendun Chophel, who revealed the corruption and degeneration of the monks and advocated for the reform of Tibetan Buddhism, was imprisoned and persecuted. He later died in prison.

Former serfs burn exploitative contracts(1959). Photo by Chen Zonglie

The feudal serfdom not only hindered Tibet’s social progress and development of productivity, but also violated the laws of development and progress of human beings.

Editor:Yanina

Tibet Stories

Put down stockwhip to become a web celebrity businessman

Lapa Tseren, who is from a family of herders, couldn’t imagine that one day, he could put d...