Abolishing feudal serfdom was a historical choice (II)

Throughout human history, slavery and serfdom have existed in most parts of the world. The two systems were renounced as backward and outdated as new ideas and enlightenment emerged in modern times, and abolitionism or abolitionist movements began to appear in many countries, ringing the death knell of slavery and serfdom. With the rise of the bourgeois revolution in Europe and the United States, the two were successively abolished in France, Britain, Russia, and the United States.

The end of the Second World War ushered in a new era of development, when peace, development, equity, justice, democracy and freedom became the goals of human society. In 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations clearly stated: “No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.” In 1956, the United Nations adopted the Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery. Article 1 of the Convention states that “Each of the States Parties to this Convention shall take all practicable and necessary legislative and other measures to bring about progressively and as soon as possible the complete abolition or abandonment of the following institutions and practices...”

On October 1, 1949 the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was founded, opening a new era in Chinese history. Under the leadership of the CPC, a new socialist system was established, making the people the masters of the country. On May 23, 1951, the Agreement of the Central People’s Government and the Local Government of Tibet on Measures for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet (hereinafter the “17-Article Agreement”) was signed, officially proclaiming the peaceful liberation of Tibet.

In view of unbalanced social development and special circumstances in some places, Liu Shaoqi, then chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC), said at the First Session of the First NPC in 1954: “Ethnic minority areas that have not completed democratic reform can complete it in some gentle manner in the future and then gradually move forward to socialism.”

In 1953, Xinjiang completely abolished all remaining feudal serfdom. Beginning in 1956, democratic reform was also carried out in Tibetan-inhabited areas of Gansu, Sichuan, and Qinghai provinces. However, Tibet at that time was still ruled by feudal serfdom under theocracy, which seriously obstructed social development and the process of civilization.

For example, before the democratic reform, the family of the 14th Dalai Lama possessed 27 manors, 30 pastures and over 6,000 serfs, and annually wrung out of them more than 462,000 kg of highland barley, 35,000 kg of butter, 2 million liang of Tibetan silver, 300 head of cattle and sheep, and 175 rolls of pulu (woolen fabric made in Tibet).

Emancipated former serfs in Tibet – the “Langsheng Mutual Aid Group” in Kyerpa Township, Nedong County (1963). Photo by Chen Zonglie

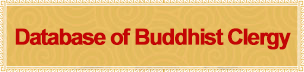

The first combine harvester arrives in Lhasa (1955). Photo by Lan Zhigui

Tibet’s first large-scale power station, the Najin Power Station after the Peaceful Liberation, was completed (1960). Photo by Lan Zhigui

However, in the “17-Article Agreement” signed in 1951, reforming the old system was included. Though there were many beneficiaries of serfdom reluctant to implement the agreement, thanks to efforts of the CPC Tibet Working Committee, after 1952, several dozen delegation of upper-class Tibetans were organized to come out from Tibet and visit other parts of China. Members of these groups witnessed the rapid development of the motherland, and some patriots underwent major ideological changes, and their concerns about reforming the old system were gradually eliminated.

A peasant from Pangcun Village of Doilungdeqen District in Lhasa recalled two incidents. In 1956, the central government invited the manor owners in Tibet to visit other parts of China, and after the visit, one of them named Chadrak Kelzang Sherab decided to free his serfs and distribute his land to them. In 1956, a Tibetan women’s delegation led by Thangme Konchog Palmo, an aristocrat, completed a trip outside of Tibet. On their return, they publicized the policies and benefits of democratic reform among the peasants in the suburbs of Lhasa, and persuaded many members of the Tibetan Patriotic Youth Association and the Tibetan Patriotic Women’s Association to stand up for democratic reform in Tibet.

In September 1957, Palgon Chogdrup, a headman in Gyantse, savagely tortured a serf called Wangchen Pungstog. Hearing of this, Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme, then a Kalon (cabinet minister) of the government of Tibet, was furious, saying, “The people in Tibet are sure to choose socialism and anxious to start democratic reform. This is what they need. They want to boost political, economic and cultural development and pursue happiness. It is also an inexorable law of human development and an unstoppable trend of progress.”

A Tibetan woman works a combine machine. Photo by Chen Zonglie

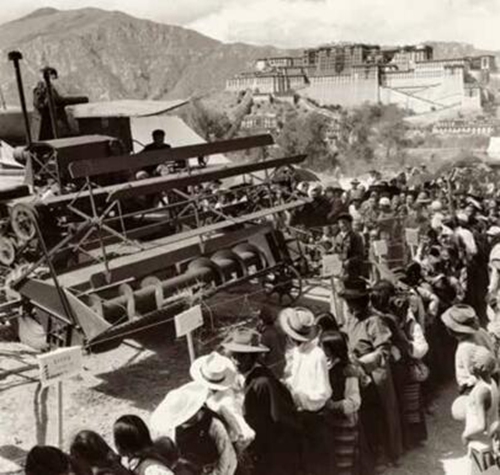

Former serfs enjoy wine to celebrate the harvest. Photo by Chen Zonglie

At the same time, the people’s growing awakening formed into a powerful force for reform. They consciously resisted the exploitation and oppression of the feudal serfdom. On July 25, 1956, some 65 peasants in Lhunzhub County of Lhasa submitted a letter carrying their finger prints to the 14th Dalai Lama, saying, “We are all peasants. We are more anxious for democratic reform than anyone else.”

Democratic reform in Tibet was a continuation of China’s New Democratic Revolution led by the CPC, and an inevitable result of the social transformation from degeneration to progress. Democratic reform was implemented progressively in the rural areas, pastoral areas, monasteries, and urban areas.

Editor:Yanina

Tibet Stories

Across China: Favorable ethnic policies bring benefits for Tibetan children

Sonam was born in Jone County of Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of northwest China's G...

Editor’s Choice

- 11th Panchen Lama: abolition of serfdom engraved in the minds of the people

- Eco-friendly toilet to be set up at 7,028m on Mt. Qomolangma

- Tibet establishes HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment association

- Panchen Lama: democratic reform an important turning point for Tibetan Buddhism

- Ranger roams reserve to protect rare golden yaks