Li Zuixiong: 18 trips to Tibet to save murals

Li Zuixiong, born in 1941, has worked for more than 50 years on education, research, and project management of cave mural paintings and ancient architecture relics. He has led 40-plus major research and international partnership collaborations, and is known as the "trailblazer and guide of Dunhuang Grottoes' technological preservation."

"We're like doctors for the cultural relics; we have to take care of them all the time," said Li. He still vividly remembers each field exploration he has made, and travels long distances to give talks to younger generations in Dunhuang, northwest China's Gansu Province.

In 1991, Li won a doctoral degree in preservation science from Tokyo University of the Arts, and became the first Doctorate in cultural relic's preservation with overseas degrees in China. After he returned to China, he has been working in cultural relics preservation and practice, and more important, in cultivating talents.

At the time, the living and working conditions in the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang were very harsh. There were only two buses a week going to the city, by which employees could buy some necessities, but they often couldn't get on due to overcrowding.

"Back then, a lot of people said the talents they brought over to Dunhuang would often leave after they went abroad for study." Li felt pressured by the remarks. When he noticed anyone who was feeling stressed, he'd talk to them.

In the mid-20th century, the caves managed by the Dunhuang Research Institute often invited some overseas experts to solve problems of cultural relics' damage and loss. But in the past 10 years, they have relied on their own talents, and have even started to export preservation experts to the rest of the country or abroad. After Li developed the preservation techniques of "modern technology + traditional materials," they began to preserve other stone caves, mural art, and cultural relic sites except for the Mogao Caves.

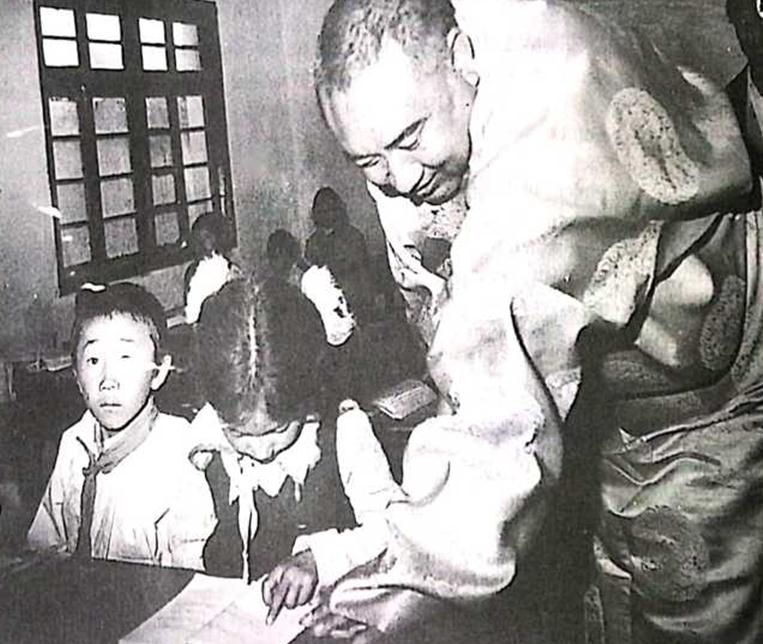

During the process of revitalizing the Potala Palace, the Sakya Monastery, and the murals at Norbulingka, Li traveled 18 times to places like Lhasa, Sakya, Ngari, and others. He led a team in rescuing almost 6,000 sqm of murals by doing environmental inspection, disease research, mural materials and disease mechanism analysis. They also focused on the features of the mural art in Tibetan monasteries by using indoor simulations and on-site experiments.

During his work in Tibet, Li was already over 60 years old. His colleagues would ask him to travel less, but they have never convinced him. Due to his frequent trips between the plains and the plateau over the years, his health has suffered, especially his heart. He even fainted many times after returning to the plains, and had to have procedures including a heart stent surgery. Whenever other people talked about balancing work and health, he'd smile and say: "I have done what I want to do."

Editor: Tommy Tan.

Tibet Stories

Why did Emperor Qianlong adopt the reincarnation system?

The system of drawing lots from a golden urn to choose the reincarnation of a Living Buddha ...